The battles of water, ice, and steam July 25, 2009

Posted by Jenny in Civil War, history, Uncategorized.Tags: Andrew Foote, Charles F. Smith, Civil War, Fort Donelson, Fort Henry, Gideon Pillow, Nathan Bedford Forrest, Simon Bolivar Buckner, Ulysses S. Grant

3 comments

This post is one of an occasional series about Ulysses S. Grant—and about Gideon J. Pillow.

The battles of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson were fought in February 1862. The weather stayed sodden over those weeks, meandering up and down around the freezing mark, and the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers flooded their channels. Fort Henry was on the Tennessee and Fort Donelson on the Cumberland, in that peculiar place where those two large rivers flowed close to each other but resisted merging before emptying into the Ohio.

By capturing the two forts, the Federals could generally control things upstream. They could blow up railroad bridges, disrupt river traffic, and occupy towns as far up as Nashville on the Cumberland and Muscle Shoals on the Tennessee. In the narrow strip between the rivers, the forts were located on broken terrain covered with bare, bleak hardwood forest where the trees threw their long shadows under the feeble winter sun. Every stream valley was filled with deep, muddy water.

The rainclouds were imitated by the puffs of steam rising from the gunboat smokestacks. The fleet had evolved halfway from the age of wood to the age of steel—some boats were all wood and some had an exoskeleton of iron—but all of these boats lived in the age of steam. They had pressure gauges, steam intake valves, boilers that might possibly explode when struck by a shell. That would of course fill the gunboat with scalding steam, as happened for instance during the assault on Fort Henry.

There was steam and rain and snow and mud. Fort Henry had been built on low-lying land by a slow-witted engineer, and it literally filled up with water at about the same time that its earthen embankments were made porous by incoming shells from the gunboats. That surrender came easily, but Fort

Donelson might have been impossible if General Pillow hadn’t helped out his foes.

The problem for the attackers on Fort Donelson was the cold. On the eleven-mile march over from Fort Henry, a lot of the Union soldiers had jauntily tossed away their heavy overcoats and blankets because it happened to be sunny and warm that morning. But by nightfall, as they camped (no tents) around the fort, it started to rain out of the dark purple sky, and then the rain changed over to snow, and the ground changed over from brown to white. They weren’t allowed to have campfires that would make their positions visible. Some of the men said later that the cold at Fort Donelson was one of the worst things they ever had to go through in the war. You might think battle itself would be worse, but that doesn’t seem to be the way things were experienced. Brute physical discomfort outweighed danger: the clothes that got soaked all the way through to the skin, the fingers too stiff to move. Bruce Catton wrote in “Grant Moves South”: Men of the 12th Iowa recalled that they spent most of the night trotting around in circles just to keep from freezing, with regimental officers improvising strange new tactical commands: “By companies, in a circle, double-quick, march!”

The next afternoon, navy officer Andrew Foote took three ironclads and two wooden gunboats splashing and puffing upriver to Donelson and attacked the fort. Foote darted in and out of the flagship’s pilot-house with a megaphone, shouting out echoey commands. But this time the defenders got the better of them. The flagship was hit 60 times, one of the shots passing through the pilot-house, killing the pilot and wounding Foote. Another vessel had its tiller-ropes destroyed. Those two vessels, both ironclads, drifted helplessly downstream like big dead turtles. The other boats had their share of damage and retreated with them.

General Pillow lost no time in telegraphing Richmond with news of a splendid victory. But even at the time, he and General John B. Floyd and the junior but much smarter officer Nathan Bedford Forrest realized they were actually in a tight spot. The Union forces encircled the fort entirely and looked as though they might be settling in for a siege. The only way out was toward the south by the road that led through the village of Dover.

The weather that night went maliciously colder. All the ruts in the muddy roads froze solid, all the men spent another night stamping and shivering and marching in little circles to stay warm. In the morning Grant was several miles away from the lines consulting with Foote when Pillow launched his assault, sending 10,000 men out to attack the Union right, south of the fort and close to the river. Within a few hours the Federals had fallen back. As Grant returned from his visit to Foote, he heard the drumming metallic sound of musketry and rode into thick clouds of gray battle smoke. He found clusters of men standing about, demoralized and lacking ammunition. The regiments on the right had suffered at least 2,000 casualties—men in blue lay everywhere, bleeding into the snow.

But ample stores of ammunition lay nearby. The inexperienced men had been too panicky to pause and refill their cartridge boxes, and their inexperienced officers had not ordered them to do so. As Grant described it in his memoir: “I directed Colonel Webster to ride with me and call out to the men as we passed: ‘Fill your cartridge-boxes, quick, and get into line; the enemy is trying to escape and he must not be permitted to do so.’ This acted like a charm. The men only wanted some one to give them a command.”

Grant thought the Confederates must have spread themselves thin on other sides of the fort, having concentrated their forces for the assault. (So simple, this observation that turned around a dark situation. So easy for anyone to

see who isn’t surrounded by the battle’s noise and confusion.) He ordered General C. F. Smith to attack the rebel line on the west side of the fort. And so Smith did, right away, in a fierce battle up a steep icy ravine. According to Bruce Catton, Smith yelled at his men, “You volunteered to be killed for love of your country and now you can be.” And his men followed him and they got through the enemy line.

At the same time, General Pillow, having broken through to the south, ordered his men back into the fort. This decision was a wonderful and mysterious thing. General Floyd reversed Pillow’s order but, after a discussion with Pillow, reversed the reversal. It seems that Pillow’s decision must have been caused by his chronic favoring of appearance over reality. He had achieved “a brilliant and brave assault on the enemy,” and now that act of the play was over and the curtain could come down. It did not seem to be connected in his thinking with the actual necessity of getting out of the fort, or maybe he thought the Union forces would wait during the intermission until he could raise the curtain on the next act, “the valorous escape of our men in gray against overwhelming odds.”

In the small hours of the night, Floyd and Pillow held a conference with the

third in command, General Simon Bolivar Buckner. Floyd was nervous about being captured, for the straightforward reason that he had taken actions as the former War Secretary that made him subject to charges of treason. So he decided to escape, and he turned over his command to Pillow. But Pillow decided that he would prefer to escape as well, so he turned over the command to Buckner, who was a responsible man and accepted it. Floyd and Pillow slunk out of the fort at 2:00 in the morning and got away in boats across the river. Bedford Forrest escaped with his cavalry through a swamp to the south, undoubtedly cursing Pillow as he went. Before dawn Buckner sent a message to Grant proposing a cease-fire and discussion of terms of surrender.

Grant’s reply became famous.

SIR:—Yours of this date, proposing armistice and appointment of Commissioners to settle terms of capitulation, is just received. No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.

I am, sir, very respectfully,

Your ob’t servant,

U. S. Grant,

Brig. Gen.

The Bunion and my fear of heights July 16, 2009

Posted by Jenny in bushwhacking, hiking, memoir, Smoky Mountains.Tags: Charlies Bunion, Lester Prong, Porters Creek

9 comments

This post is dedicated to my former husband, Christopher E. Hebb, who died of a brain tumor in 2004. We’d been out of touch a long time when he passed away—our marriage had ended amicably years before—but he left an indelible and positive impression on my life.

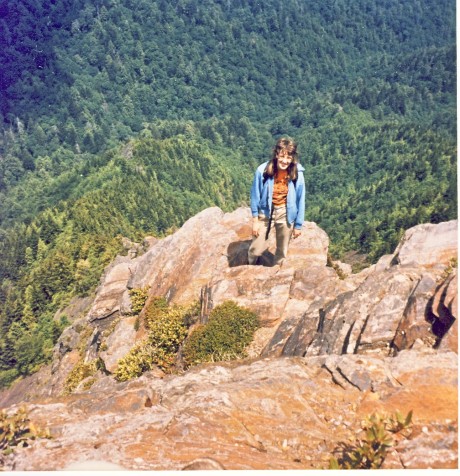

Chris and I moved to Knoxville in 1982 when he entered the clinical psychology program at the University of Tennessee. As soon as we arrived, we were doing a lot of hiking in the Smokies. Since we had done some technical climbing together—he was much better at it than I was—we soon started talking about climbing Charlies Bunion from the bottom, out of the Greenbrier.

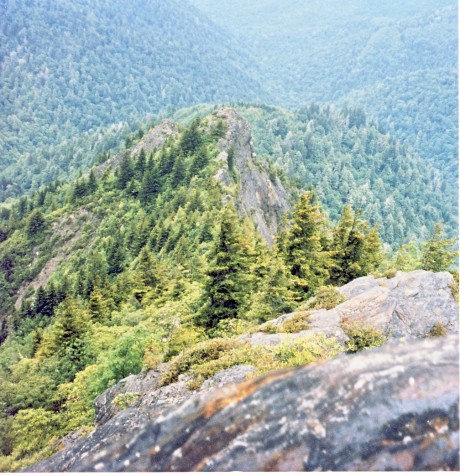

As I have described in other posts, Porters Creek and Lester Prong in the Greenbrier form pathways for rockhoppers that lead to mysterious and difficult places. Depending on which fork of Lester Prong you follow through the giant trees and cascading streams of the Greenbrier, you end up on the “real” Bunion, the “tourist” Bunion, or the “Jump Off.” The “real” Bunion is what the Smoky Mountains Hiking Club calls the place labelled as Charlies Bunion on the far lefthand side of the USGS Mt. Guyot quad, and I have described that here. The “tourist” Bunion is the place with the little circular trail around the top, on the right side of the LeConte quad, the place most people think of as Charlies Bunion. That is the place Chris and I were talking about going, but not from the A.T.

Chris and I decided in the late summer of 1983 to climb the Bunion from the bottom. We’d do it as an overnight trip. I knew that for me it would be hard because of my fear of heights, but I still thought it was doable. We backpacked up the Dry Sluice Manway to the junction of Porters Creek and Lester Prong, and we followed the stream a short distance to the tributary we would take to climb the Bunion. It had been very dry in the weeks before our trip, so we were able to stay right in the stream.

We set up camp near the stream junction, and I thought about how streams form paths in wild places, how you have to pay attention where they diverge, because a junction may lead to destinations as different as night and day. It’s like the fairy tales of childhood where you watch the hero journey through treacherous places and you think, “Oh no! Don’t go that way!” because you know, and he doesn’t, what lies at the end of that path.

That evening we listened to the beautiful song of a bird high up in the trees. The notes dropped down from the branches like small silver balls. The green gloom thickened as we sat quietly beside our tent, surrounded by shadows. When I looked across the stream valley to the slope on the other side, I felt something like exhaustion to see so many rotting treetrunks that had been there for years, to look at the brush that would take hours to work a way through it.

We passed the night encapsuled in our small warm cocoon while the woods breathed the night air and animals rustled on the forest floor. The stream ran musically down its rocky course.

In the morning I awoke with an indigestible ball of apprehension in my stomach. I watched Chris as he boiled up the water for our oatmeal. He was wearing an orange t-shirt that said “Psycho-canoeists of the North,” a white floppy hat with a green brim that had been worn on our backpack up the Abol trail on Mt. Katahdin (!), and khaki pants from an army surplus store. I felt better when we started moving up Lester Prong. We left our backpacks behind and carried small daypacks—we would circle back around and pick up the larger packs on the way out.

After we turned up the tributary, the streambanks quickly steepened so that we were travelling up a narrow cut gouged by floodwaters. We soon arrived at our first obstacle, a small cliff that ran across the streambed from side to side, blocking the V-shaped draw. At its base lay a deep pool. But you could find a way to the side if you braced your feet and back against rocks and chimneyed your way up.

The streambed was choked with logs and brush that had been swept down in various floods, making for hard going. Chris suggested getting up onto the ridgecrest. I peered up at the slope to our right. It was very steep, and I had no idea what it would lead to. But I looked at it only a moment before I started to climb. Already I had reached a spellbound state. Even though I thought it possible something awful could happen, I’d made up my mind to do this climb. I was somehow able to shut off a whole level of thinking that involved weighing, worrying, and considering.

It was, to say the least, extremely steep. We sweated our way up a short distance, and suddenly it was not a matter of exertion any more, it was a question of choosing the right move. We found ourselves nose to nose with the Anakeesta’s familiar thin brittle layers. Unfortunately, we were moving in the same direction as the grain of the rock, which made for fewer handholds: the layers ran up and down as we climbed instead of across, so that we didn’t have steps, we had vertical grooves.

The place gave me a deep sense of uneasiness. I didn’t look down, I didn’t look up, I just moved from one section of rock to another, grabbing onto a handy bush here and there. Chris, on the other hand, refused to touch the vegetation, upholding the rockclimber’s ethical standard of “no vegetable holds.” And it really wasn’t necessary to use the bushes to pull myself up, it was just a form of security. My world right then was just vivid blue sky, brown rock, green shrubs, and the scrabbling of my boots as I felt for a foothold.

Finally we reached the ridgecrest, a pleasant place covered with blooming rhodo. All at once everything felt much more secure, as if something that had been upside down had just been turned rightside up. I wasn’t struggling any more to keep from sliding or falling, I was standing surrounded by high rhodo that gave me a sense of being protected.

We were standing on the back of a whale in an ocean of trees. Then we turned and looked at what we still had to climb. The ridge stayed brushy for a while but steadily narrowed, steepened, and turned to bare rock. I actually looked away, feeling the menace of the place.

We started up the humpbacked ridge. The rhododendron made an arbor that let in a cool, speckled light. Most of the time we had to bend over or crawl to squeeze under the arching branches. It was a secure, enclosed little world surrounded by gaping space. Every now and then we came to small bits of exposed rock that gave us a taste of what was to come.

I continued to work my way over these short rock pitches in my spellbound state, completely absorbed in what I was doing. Each obstacle flowed toward me, towered over me, then receded behind me as I overcame it and moved on to the next one.

At the open spaces we had an increasingly detailed view of what stood between us and the top. We were getting closer now to the stone staircase that climbed straight up the shadowy mountainside. The bright morning sky glowed behind the jagged ridges, behind the fortress that lay ahead.

We came out onto open rock. Everything was changing again. Just as when we reached the crest of the ridge, we were turning a page, entering a new landscape in which the giant physical shapes around us had shifted. The proportion of air to rock here was high. As I climbed, I sensed a fear that hovered nearby, but there was an interesting sense of detachment between me and the fear.

Somehow I was able to think about what was there, the support the rocks offered, instead of what was not there. I would continue to have three or four points of contact with the rock. My fingers felt for the thin horizontal ledges, for now we were climbing across the grain of the rock rather than parallel to it. I was amazed to realize that I felt happy. How many chances do we have to be surrounded by sky? To be in this place was like having a vision that kept getting deeper with each step.

All around us, ridges and ravines showed sharp edges in morning shadow and light. We climbed up the warm rock, past the small scrubby myrtle that grew here and there, toward the final hump that has the tourist path around it. We reached the path and met a family perched on the rock. Of course they asked us where we’d come from. “From the bottom,” we said, crossing the path and continuing up the other side until we reached the very highest point, where we stopped to have lunch. I had been afraid, but it hadn’t stopped me.

The fork in the gully July 13, 2009

Posted by Jenny in hiking, literature, spy novels, travel.Tags: Boer War, Department of Information, Greenmantle, John Buchan, Mr. Standfast, Scotland, The Three Hostages, Thirty-Nine Steps, World War I

1 comment so far

John Buchan, the author of The Thirty-Nine Steps, liked to set his characters desperately running across dangerous mountains. He was the best describer of mountain landscape of any novelist I have read. He understood about ridges and gullies, headwalls and scree slopes. And he seemed more interested in places like the boilerplate slabs of the Black Cuillen than, say, the north face of the Eiger or the heights of Everest, which have gotten very overexposed.

I was thinking about Buchan lately because I came across a negative description of him in a history of World War I, The Pity of War by Niall Ferguson. Buchan was apparently very active in churning out propaganda for Britain’s Department of Information. And I can hear a tinny sound in his voice, the note of the propagandist, when I read a work like Greenmantle, published in 1916. The worst problem with Greenmantle is not the references to battle or “looking forward to being in at the finish with Brother Boche.” It’s the characters made out of tinsel: “As she stood with heightened colour, her eyes like stars, her poise like a wild bird’s, I had to confess that she had her own loveliness. She might be a devil, but she was also a queen.” Oh, dear.

I kept myself amused while turning the pages of Greenmantle by testing myself on all the references to the Boer War and the 1914 Maritz Rebellion— for one of the leading characters, Peter Pienaar, is said to have been born in Burgersdorp in the Cape Colony. That’s a good choice—makes Pienaar a British citizen but from a pro-Boer town near the Free State border. Buchan, like many other British subjects who spent time in South Africa during or soon after the war, seems to have been divided between admiring the veldcraft of the Boers and insisting on the noble cause of the Empire. Pienaar is described as a consummate outdoorsman, but: “When the Boer War started, Peter, like many of the very great hunters, took the British side and did most of our intelligence work in the North Transvaal.” Well, yes, probably because all of the great hunters’ clients would have been wealthy Brits.

Actually, the best part of Greenmantle is the section where Peter Pienaar and Richard Hannay are pretending to be followers of Manie Maritz who are now selling their services to the Germans. And that’s not just because I’m interested in the South African references. It’s because the other thing that Buchan does really well, apart from writing about mountains, is convey the sound of a smart, world-weary traveler who’s been knocking around the globe, in much the same way you find in Somerset Maugham or Graham Greene: “His clothes were of the cut you might expect to get at Lobito Bay…. I talked Portuguese fairly well, and Peter spoke it like a Lourenco Marques bar-keeper, with a lot of Shangaan words to fill up. He started on curacoa, which I reckoned was a new drink to him…” And so on. This stuff is all good and durable, a picture of a long-gone world.

The mountains in Greenmantle are in the wilds of eastern Turkey near Erzerum. I don’t know if Buchan ever spent time there, but he seems to have been less than thoroughly familiar with that region, so he made the mountains look like South African ones, complete with precipitous krantzes. He does better with mountains in Mr. Standfast, where he visits the Black Cuillen of Skye, and in The Three Hostages, where his character Hannay fights it out with the villain in the Scottish highlands.

His place in the highlands is called Machray, and as far as I can figure out, it is a composite of some real places. He names the following mountains: Stob Ban, Stob Coire Easain, Sgurr Mor, and Sgurr Dearg. Two could be in the Mamores, one on Skye, and two elsewhere in western Scotland. (The names seem to be common ones that mean things like “white peak” and “big peak,” and are found more than one place in Scotland.) Sgurr Dearg is famous for the “Inaccessible Pinnacle” that rises from it. (All of the photos in this post are from Wikimedia Commons—places I’d love to go but haven’t been.)

At the end of The Three Hostages, Richard Hannay is climbing up a gully on the looming, precipiced mountain of “Sgurr Dearg” with the enemy, Medina, coming after him. One of the two, you can easily see, is not going to come out of this alive. Hannay scrambles up the gully, working around “a rather awkward chockstone,” and comes to a fork. The left branch looks hopelessly difficult, and the right seems to offer more handholds. But then Hannay recalls looking at the same gully from a higher ridge, on a previous trip:

I had come to the conclusion that, while the left fork might be climbed, the right was impossible or nearly so, for, modestly as it began, it ran out into a fearsome crack on the face of the cliff, and did not become a chimney again till after a hundred feet of unclimbable rotten granite.

So he goes up the left and manages to claw his way around some obstacles on “an extreme poverty of decent holds.” After various dramatic vicissitudes, Medina tries to follow, but he takes the wrong fork—he goes for the one that starts out looking more doable but that ends on the impossible face. And Medina falls to his death.

What I really like about this episode is that there is no moral symbolism in taking the wrong fork. Buchan is not saying, “Medina took the way that looked easier, and so naturally he ended up failing because it is morally superior to go the harder way.” He is just narrating the way a path in life can have an unpredictable fork. The slant of the propagandist is not evident here, in a place where it would have been easy to throw in some grandiose higher meaning. I don’t mean that the book could have been literal propaganda (The Three Hostages was published in 1924), just that the mindset is sometimes hard to get rid of.